The National Museum of Rome, which possesses one of the world’s most important archaeological collections, is housed in three different facilities: the Baths of Diocletian, which include the Octagonal Hall, the Palazzo Massimo, and the Palazzo Altemps.

The historic headquarters of the Museum is the Baths complex built by Diocletian between the last years of the third century and the beginning of the fourth century A.D. (the dedicatory inscription dated 306 A.D. is conserved in a fragmentary state in the Museum). The building of the Baths, the largest in the ancient world, included many rooms besides the traditional calidarium, tepidarium and frigidarium — which were designed to hold 3.000 people at the same time.

National Roman Museum: The Baths of Diocletian

The Roman National Museum, housed in the halls of Diocletian’s Baths and rooms of the former Carthusian monastery formed by converting part of the baths, is approached through a garden where steles, sarcophagi and reliefs are on display.

In the museum contains extensive archaeological finds from the early period of the Latin tribes, starting with the first traces of settlement and continuing to the rule of the Etruscan kings in the 7th century BC. Showcases and high-quality maps illustrate the everyday world of the Latin people with household pottery, everyday items, tools, weapons and many burial objects.

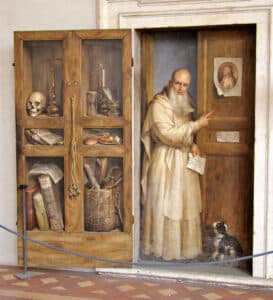

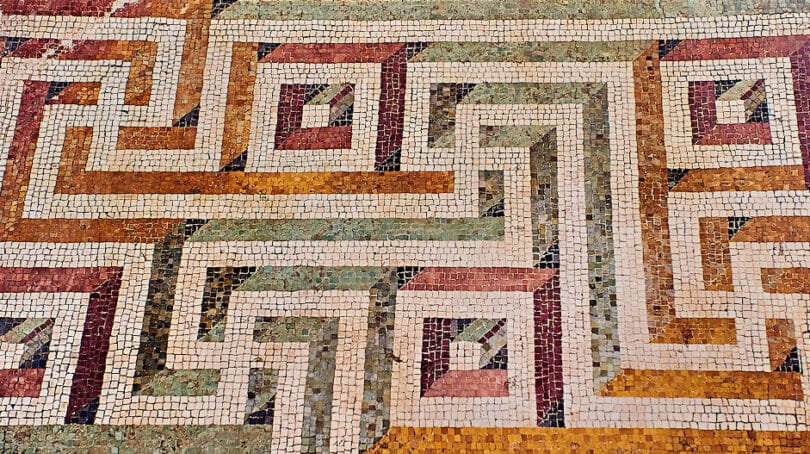

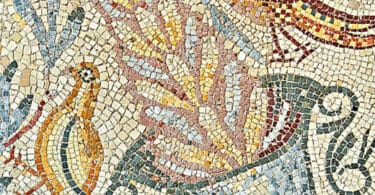

The ceramic urns used for funerary rites, in the form of a circular hut with animal decoration on the ridge as a protective spell, are very unusual. The cloister with its fountain and colonnades, conceived by Michelangelo and completed in 1565, is adorned with marble sculptures, architectural fragments, mosaics and inscriptions.

National Roman Museum: Octagonal Hall

The Octagonal Flail stands at the southwest corner of the central complex of the Baths of Diocletian, in which it may have served as a passage area. In 1929 it was transformed into a Planetarium by Italo Gismondi. The hall recently underwent a thorough restoration that brought out all the beauty of the nearly intact octagonal setting, with its four semi-circular niches in the corners and the umbrella-shaped cupola with the central opening. The diameter of the hall is 22 meters. The restorers have preserved the iron structure that supported the ceiling-map of the heavens, in part because of its uniqueness, but also as a memento of the hall’s past history as a planetarium.

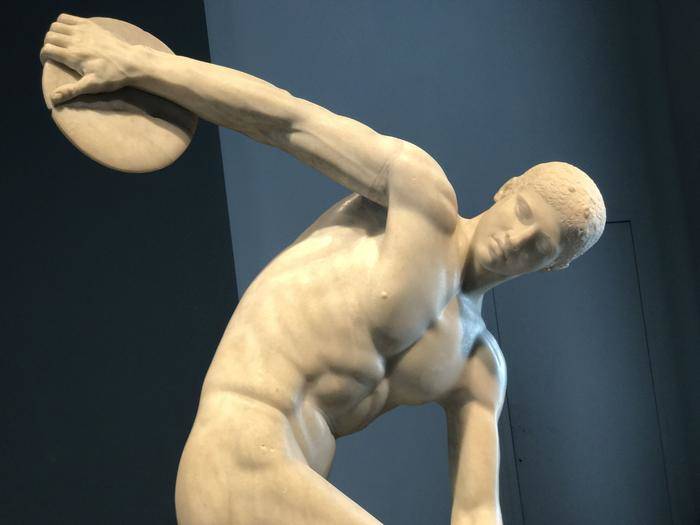

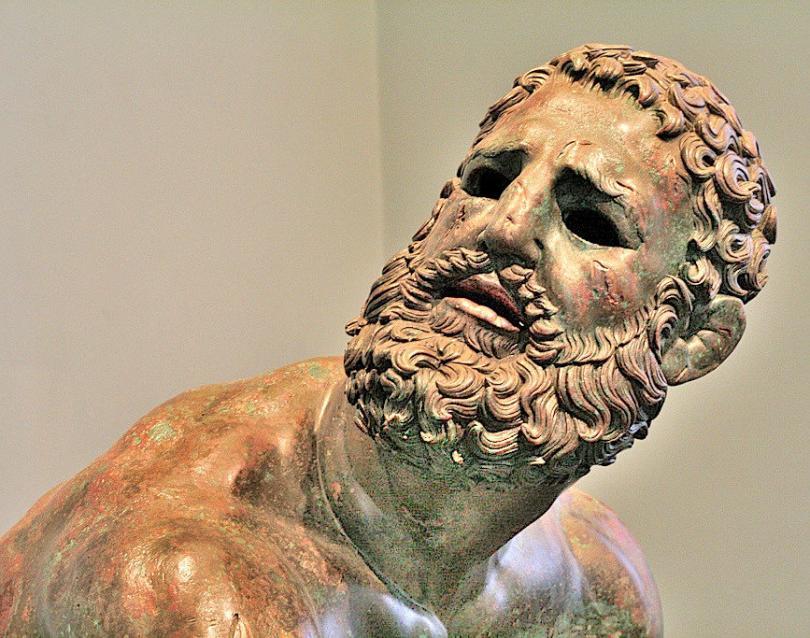

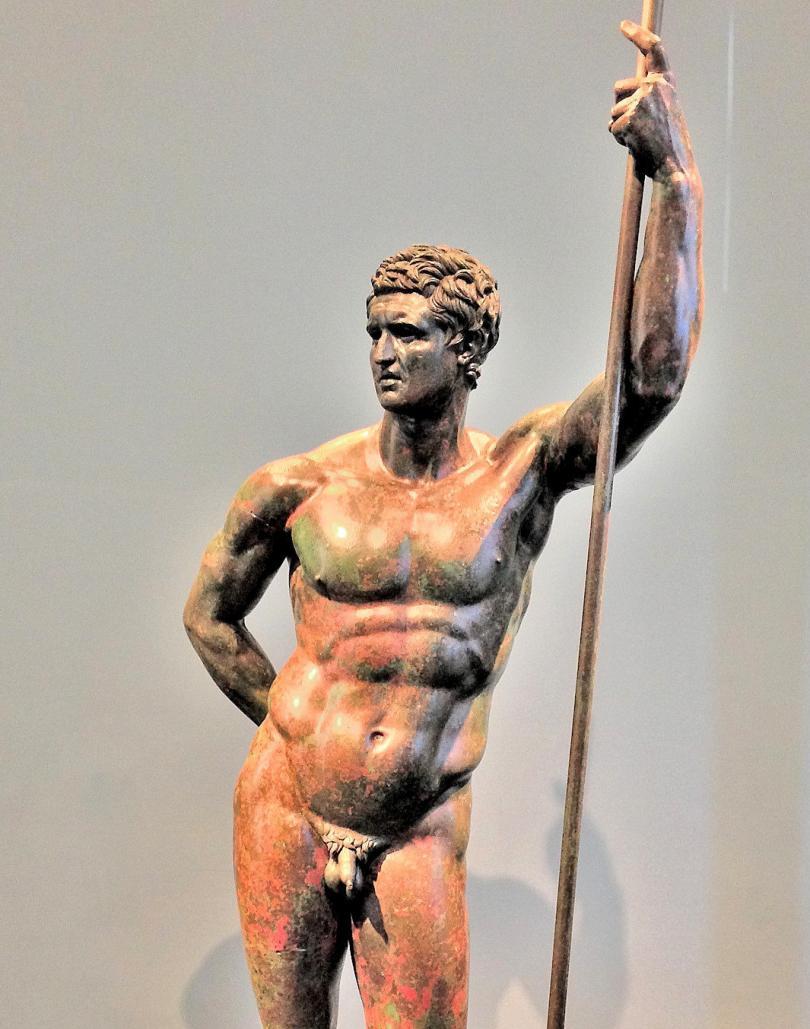

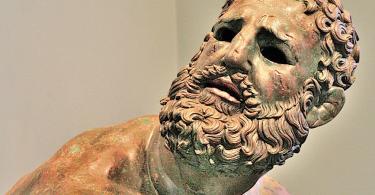

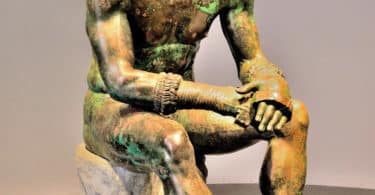

The Aula Ottagona gives an almost authentic impression of how the magnificent domed rooms of the enormous Baths of Diocletian must have looked. This room was originally the Sala della Minerva of the palaestra in the baths. Framed by numerous marble statues, Roman copies of Greek originals from the municipal baths of Rome, the two bronze sculptures in the centre of the hall immediately catch the eye: a larger-than-life, standing Hellenistic Prince (2nd century BC) with a muscular, idealized body, and an exhausted, Resting Boxer (late 4th or early 2nd century BC), represented in brutal realism with a bleeding eye, broken nose and lacerations on his body.

National Roman Museum: Palazzo Massimo

Formerly the site of the preparatory school “Massimiliano Massimo”, the building was constructed in 1883-87 by Camillo Pistrucci in imitation of the noble residences of the early Roman baroque period. In 1960 the school was transferred to another facility and Palazzo Massimo fell victim to neglect; not until 1983 was it purchased by the State and designated as the site of the National Museum of Rome after undergoing years of complex restoration.

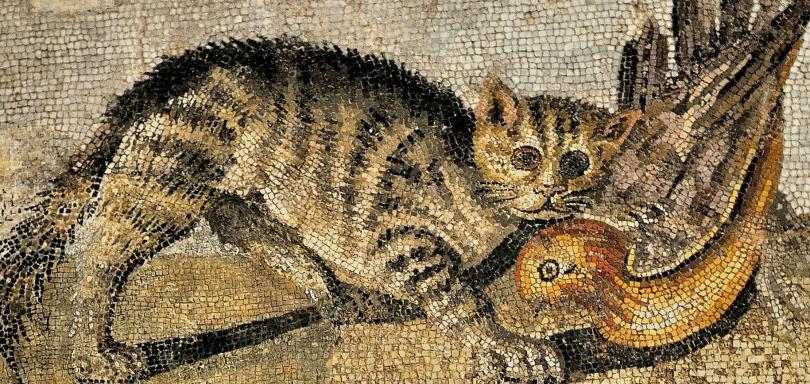

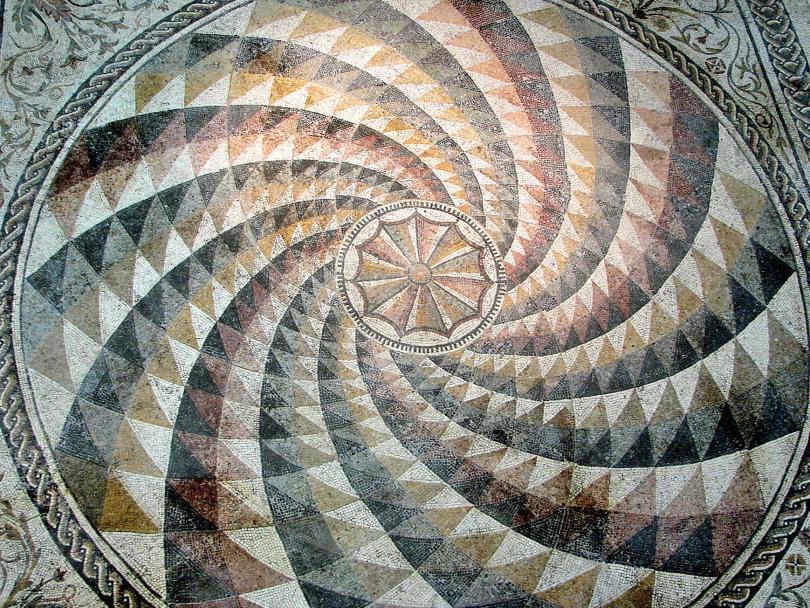

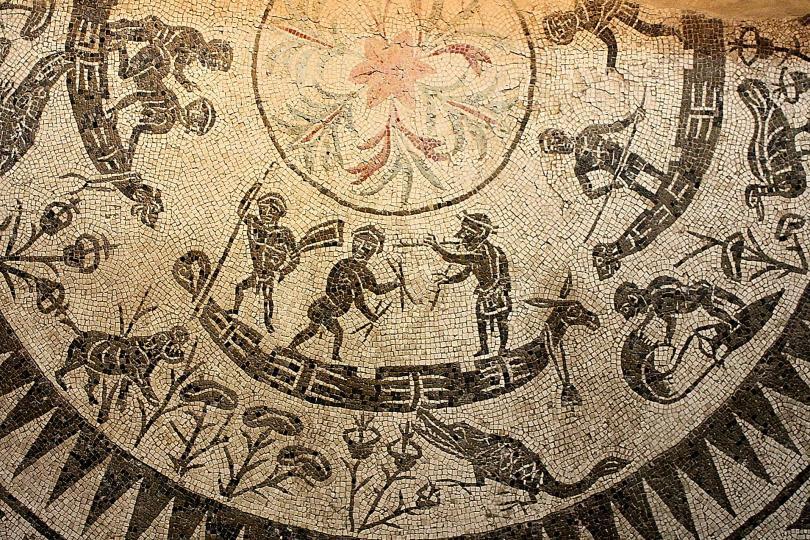

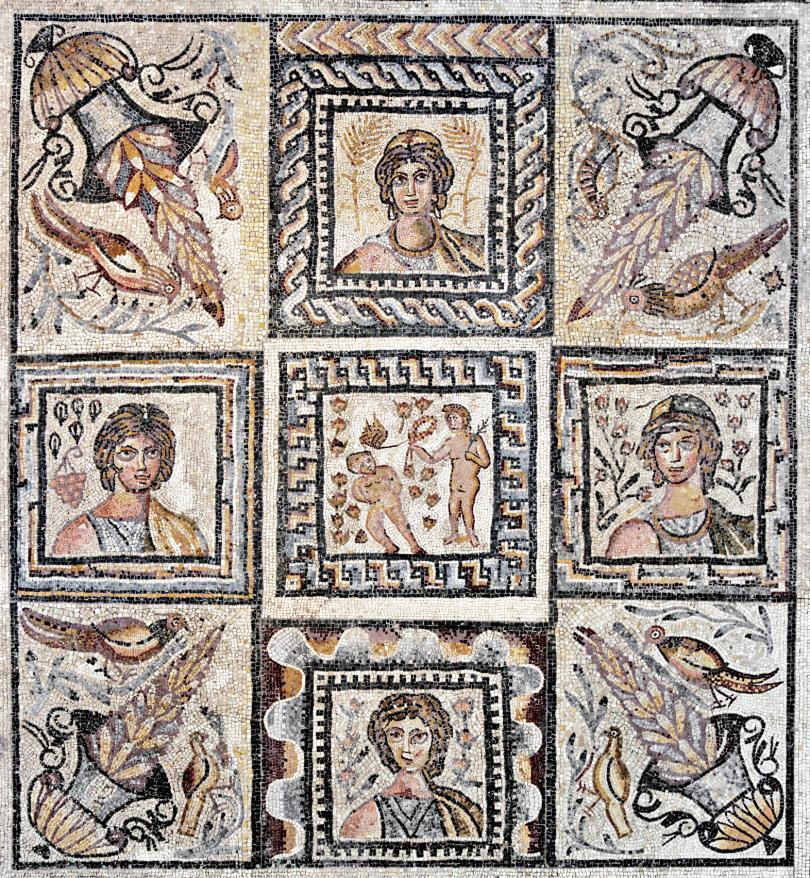

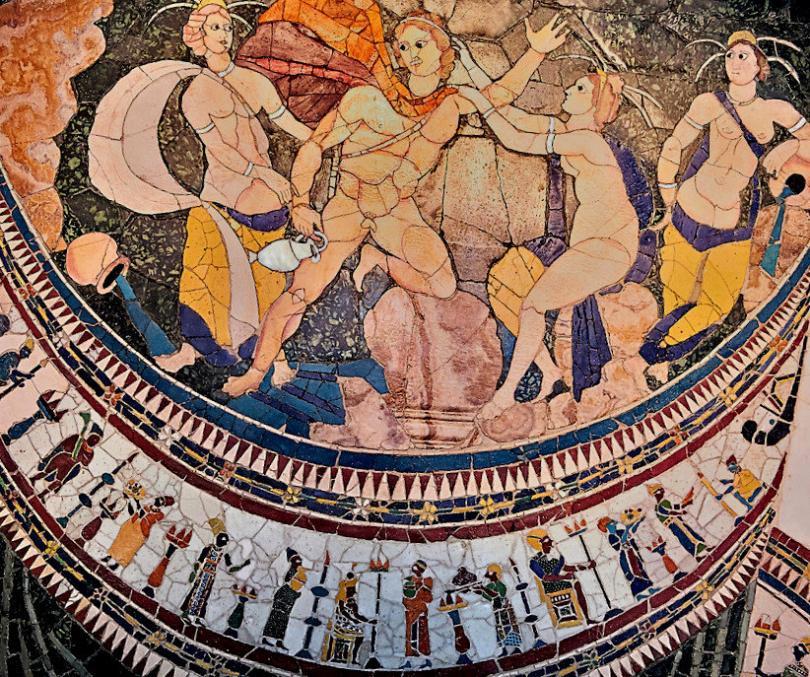

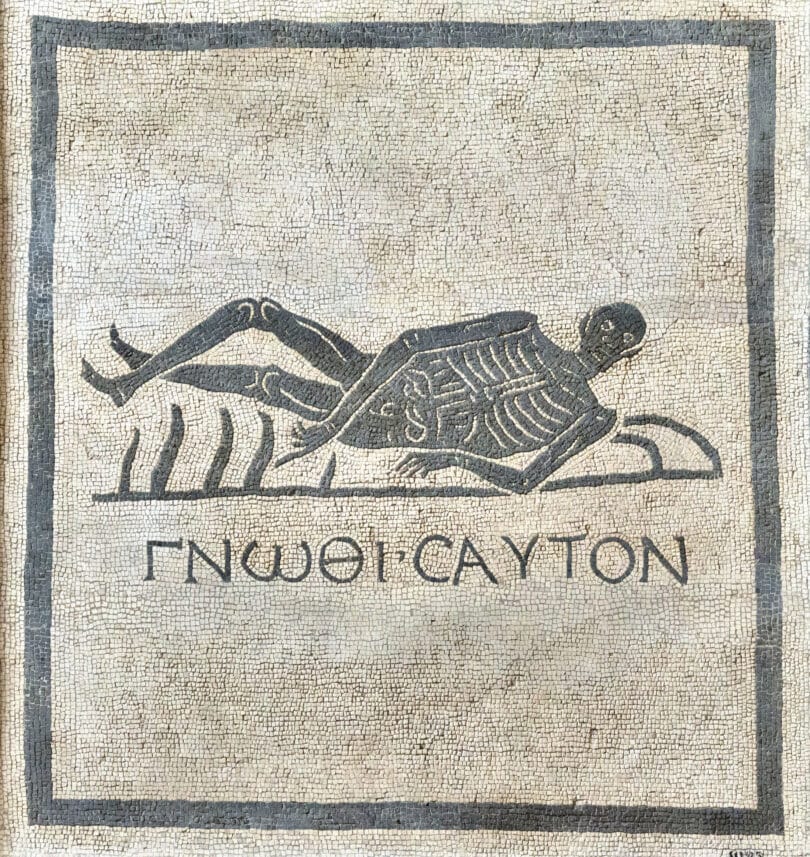

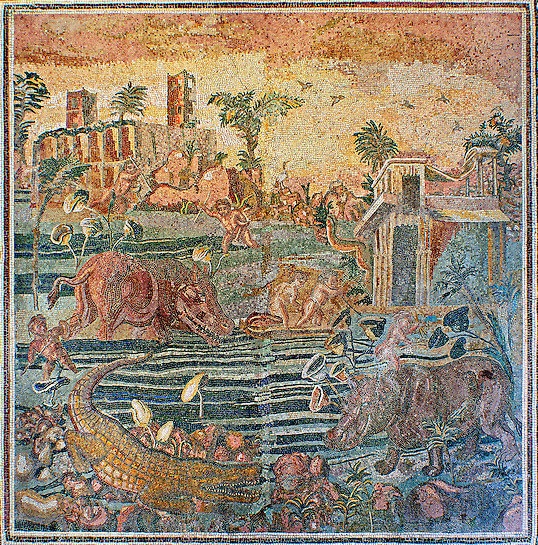

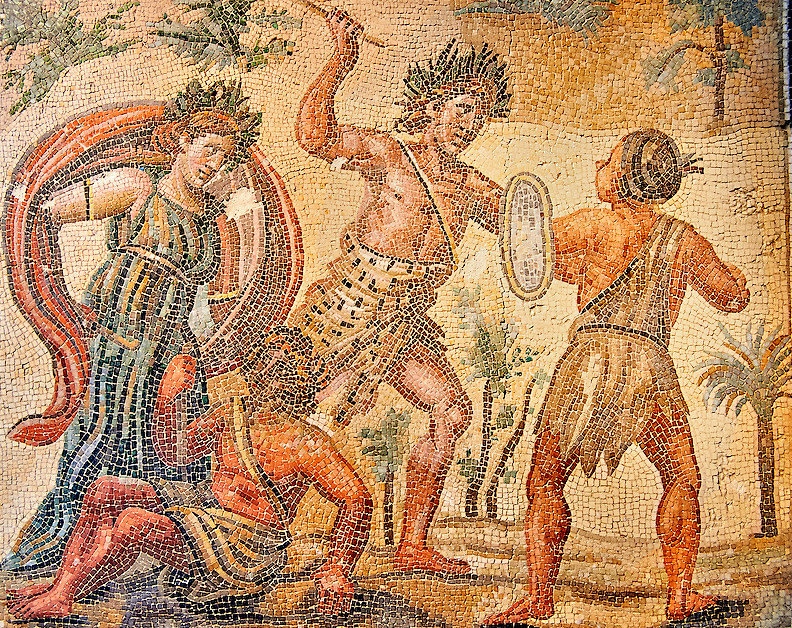

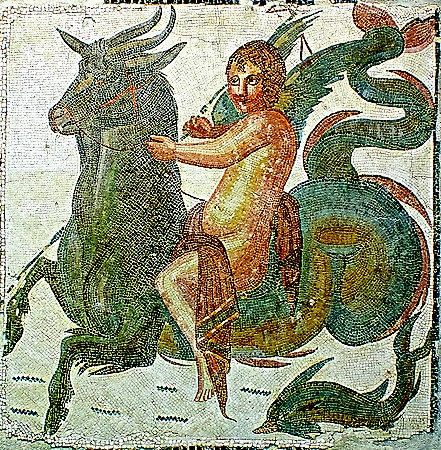

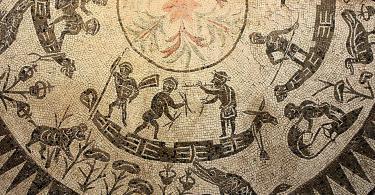

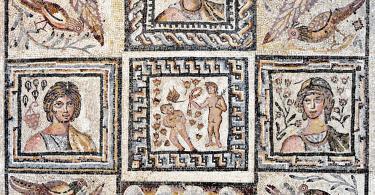

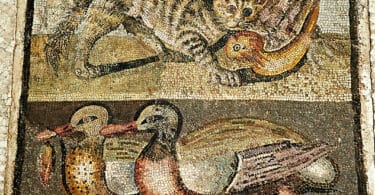

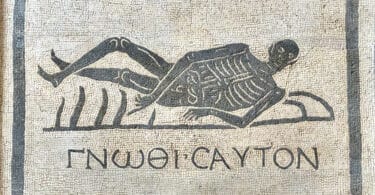

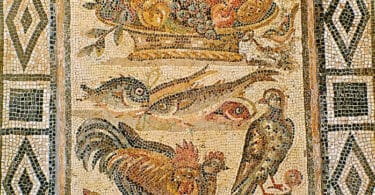

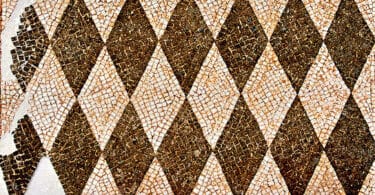

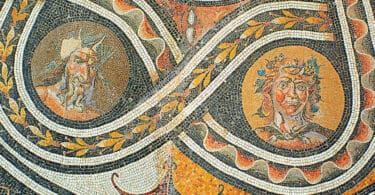

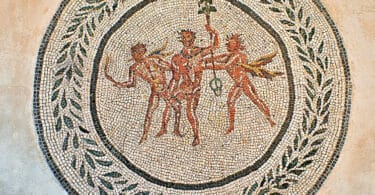

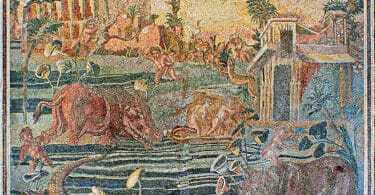

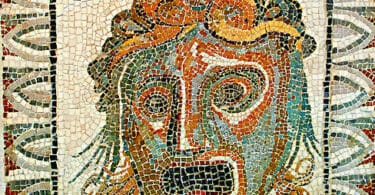

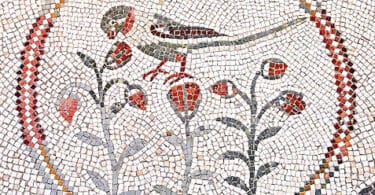

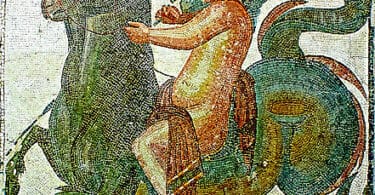

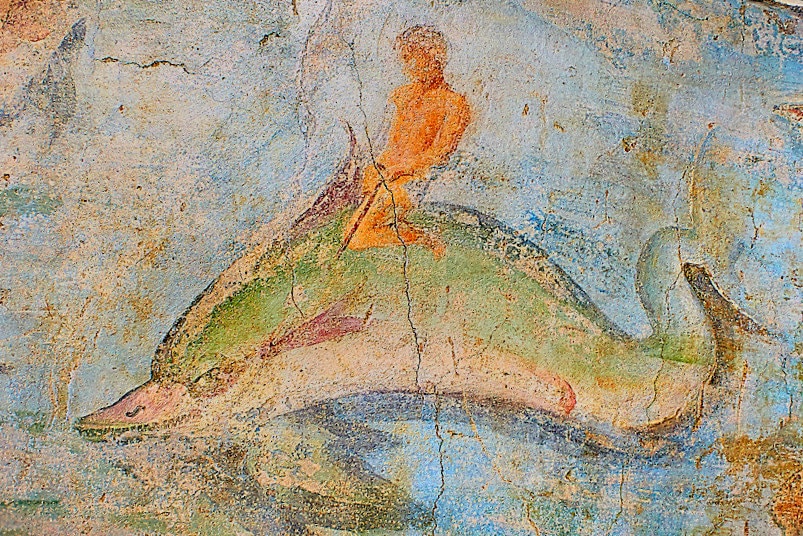

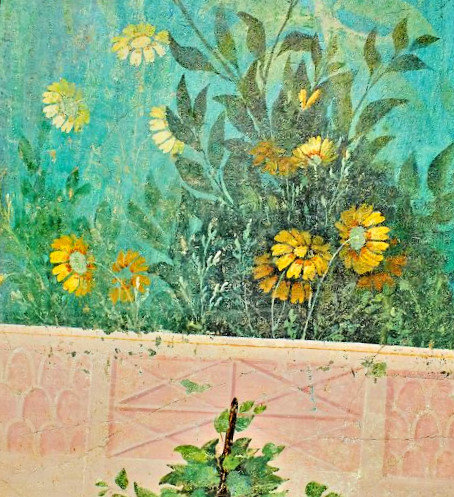

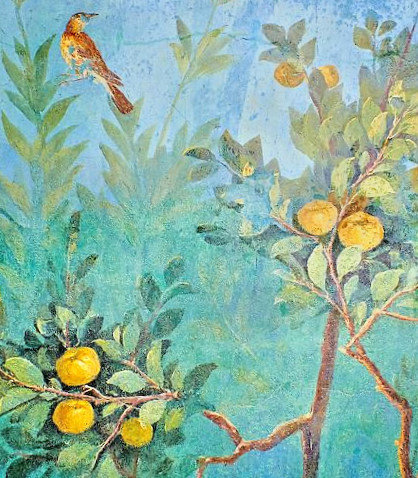

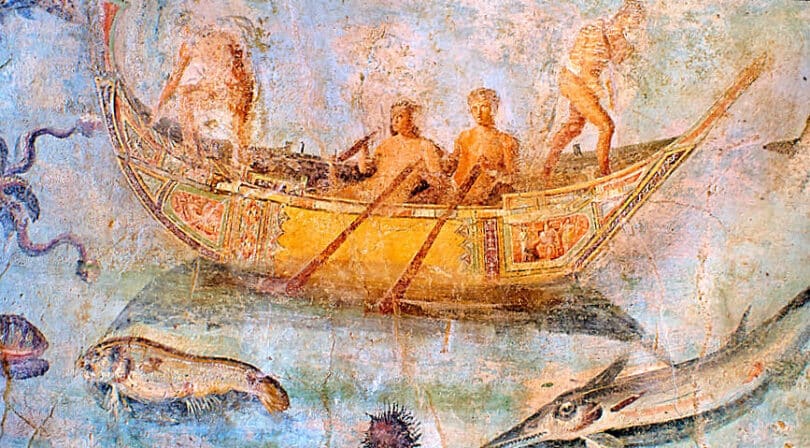

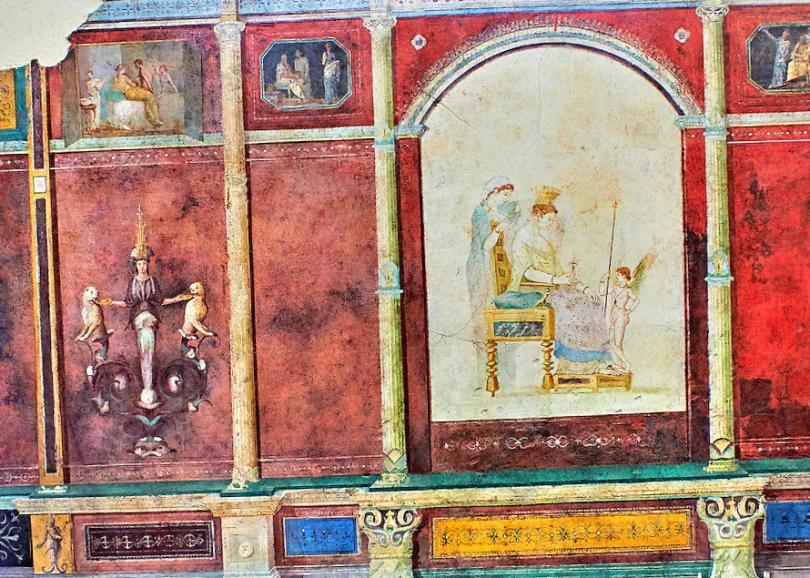

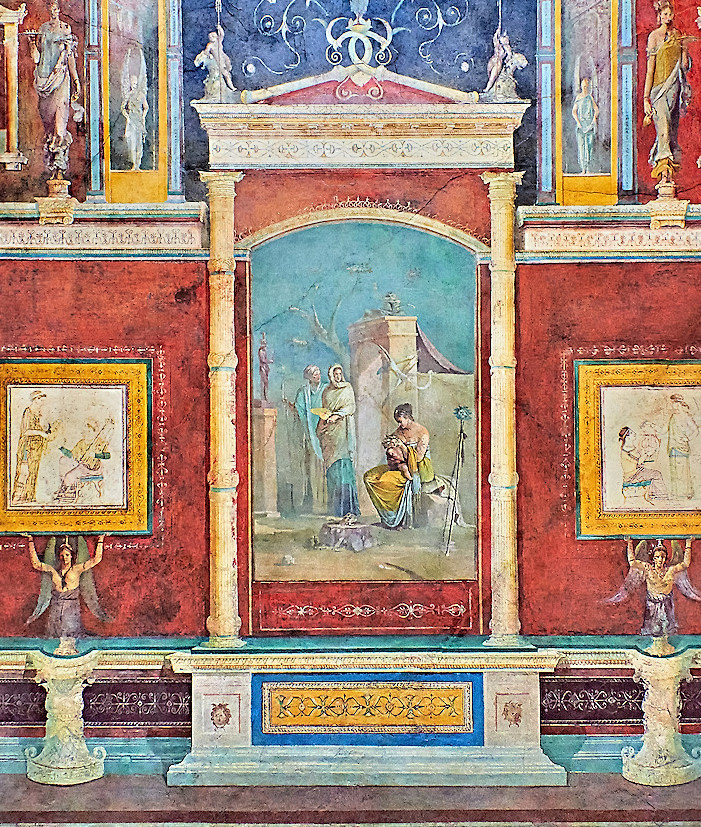

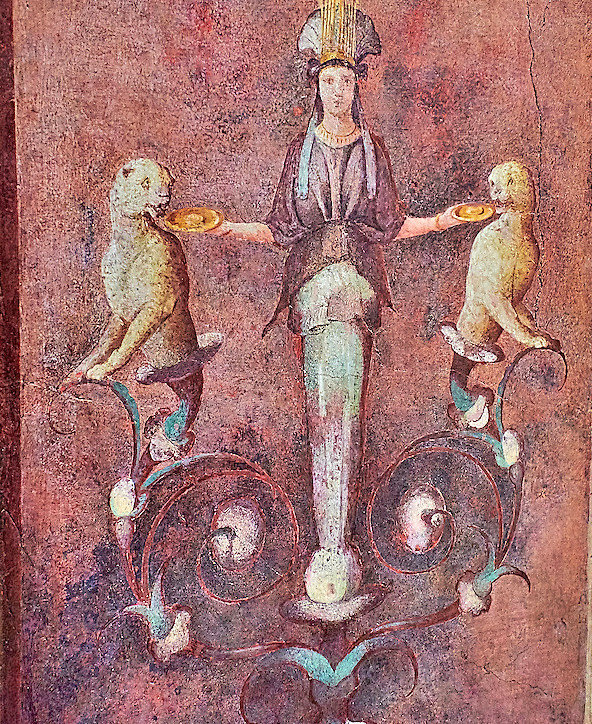

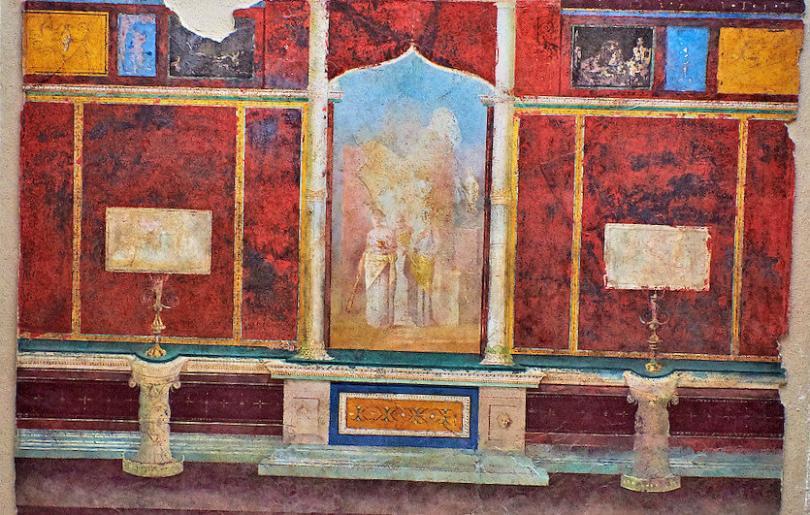

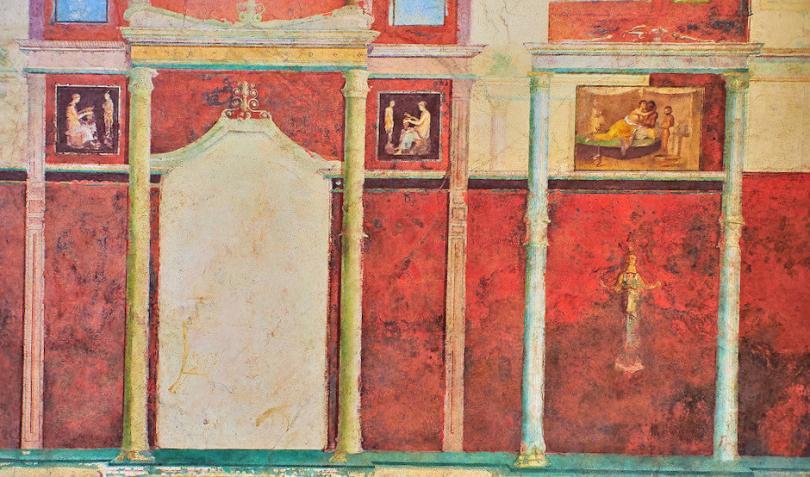

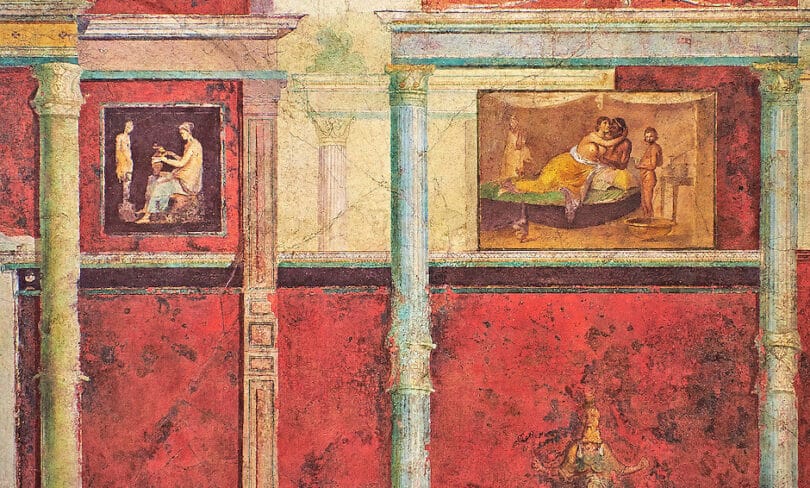

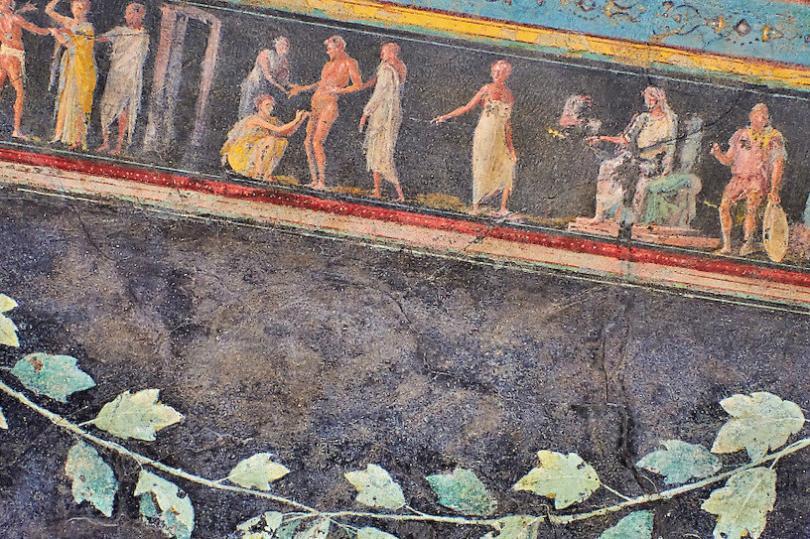

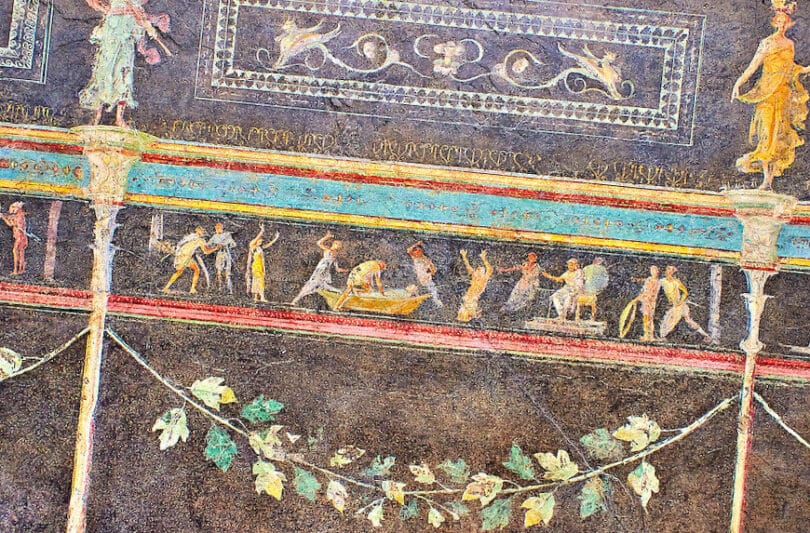

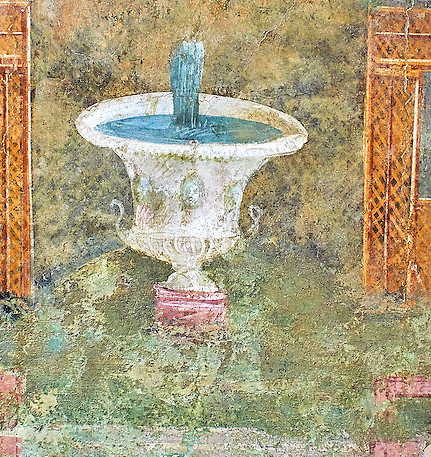

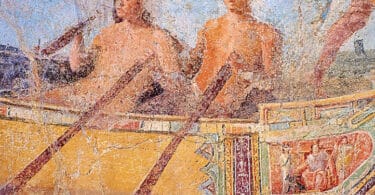

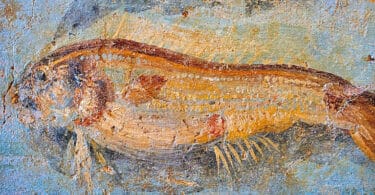

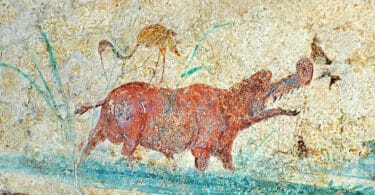

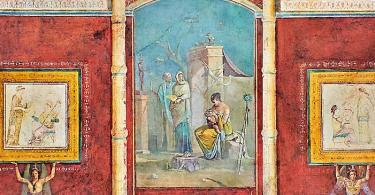

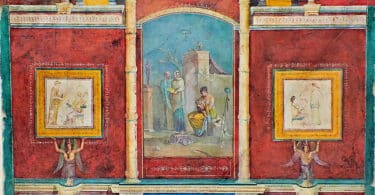

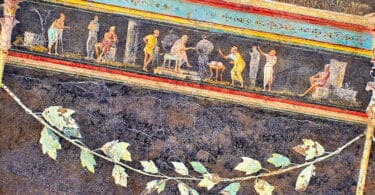

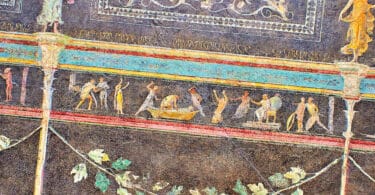

The collection at Palazzo Massimo alle Terme forms part of the National Roman Museum. It mainly displays material from the splendid houses of the senatorial class in Rome. These works, when viewed together with the items from the imperial palaces displayed at the Museo Palatino, provide a comprehensive panorama of the art of late republican and imperial Rome. The second floor of the palace is wholly devoted to a display of the most significant examples of Roman decorative painting and mosaic pavements found in Rome and Lazio, including some recent discoveries.

Mosaic Collection – Photo Gallery:

The display includes reconstructions of some interiors of important residential complexes, such as Livia’s villa at Prima Porta and the Villa della Farnesina on Via della Lungara. In particular the reconstruction of some interiors with the frescoes on the walls and stuccoed vaulting reveals the conceptual unity of the decoration, which is usually seen only as fragments.

The ground floor of Palazzo Massimo contains examples of iconography and portraiture from the late republican period, with a display of sculptural decorations from the residences of the wealthy classes. Many statues are Roman copies of Greek originals by great sculptors such as Lysippus and Praxiteles (both fourth century BC).

Frecoes – Photo Gallery:

The basement level has sections devoted to numismatics—covering ancient times, the Middle Ages and the present and a display of jewels and household items made of precious materials, mostly from imperial times. The artefacts mostly come from tombs regularly excavated, so the objects can be dated and understood in their cultural and historical setting and not viewed merely as collectors’ pieces. Among the exhibits is an unusual example of the embalmed body of a little girl with her tomb furnishings from Grottarossa (second century BC).

National Roman Museum: Palazzo Altemps

In the second half of the sixteenth century Cardinal Altemps decided to transform the family palace, under construction for a century, into “a home for statues.” Subsequently, however, the cardinal’s collection of ancient sculptures and his rich library were dispersed, a destiny shared by the majority of the patrician collections, which frequently changed hands.

Ancient Roman Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus at Palazzo Altemps, dating to 260 AD, is known for its densely populated composition of the battle between Romans and Goths.

Marble statue of Aphrodite by Cnidus at the Palazzo Altemps. Ancient Roman copy after a Greek original of the 4th century.

The building contains sixteen sculptures that once belonged to the Altemps collection and items from other important collections, like the Boncompagni Ludovisi and Mattei collections and the Egyptian collection of the Museo Nazionale Romano. The antiquarian reconstruction of the original Cinquecento setting was suggested by the close relations between the Ludovisi and Altemps collections, with pieces passing between the two families. Restoration of the interiors now enables visitors to admire the splendid statues at the same time as they view the magnificent building that houses them.

SOURCES:

- Resting Boxer – Photo Credit: Met Museum

Leave a Comment