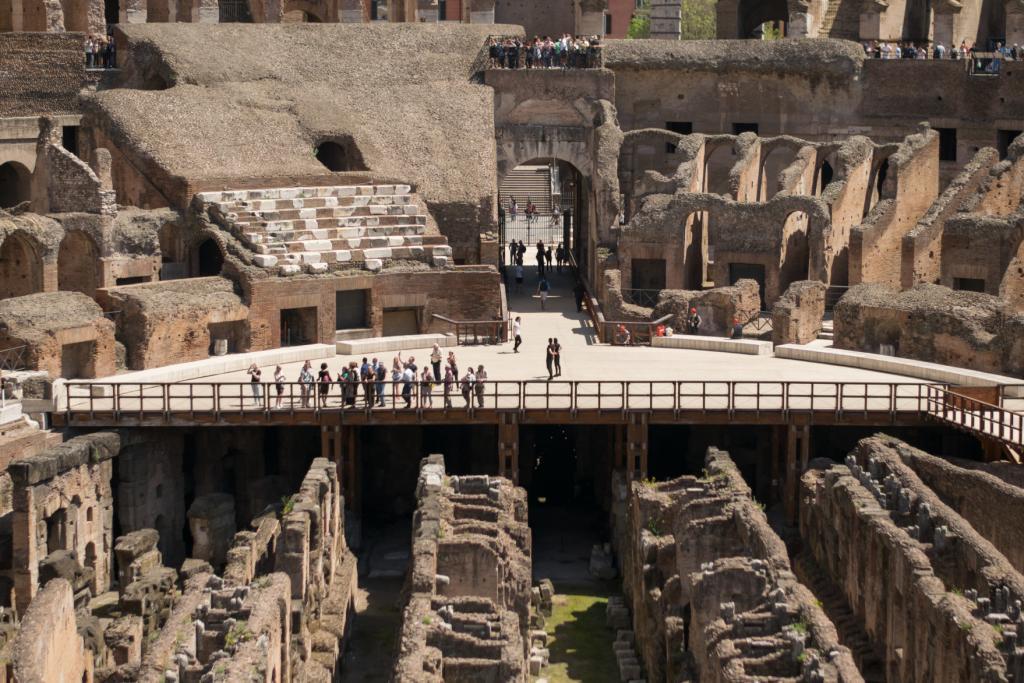

In the early 5th century, devastating earthquakes struck the Colosseum, profoundly weakening its structural integrity. As debris accumulated in the hypogeum—the complex network beneath the arena floor—its underground chambers gradually became buried. With each passing decade, maintaining this vast amphitheater proved increasingly challenging, especially as the city’s ruling elite, now predominantly Christian, viewed gladiatorial combats with growing disdain. After all, who would willingly fund spectacles they morally opposed?

This ideological shift, combined with structural decay, led to the gradual abandonment of the amphitheater’s original purpose. As centuries unfolded, the Colosseum transformed from Rome’s vibrant entertainment hub into a convenient resource for construction materials. If you’ve ever wondered why the monument appears riddled with holes today, it’s precisely because metal brackets, once binding the massive travertine blocks, were systematically extracted and reused elsewhere.

Over time, the building faced substantial deterioration, particularly evident on its southern side, where the outer wall was largely dismantled—a stark contrast to the relatively preserved northern facade. Interestingly, the north side survived due to its strategic placement along a critical urban route connecting the Palatine Hill, the political heart of ancient Rome, to the Lateran, the papal seat.

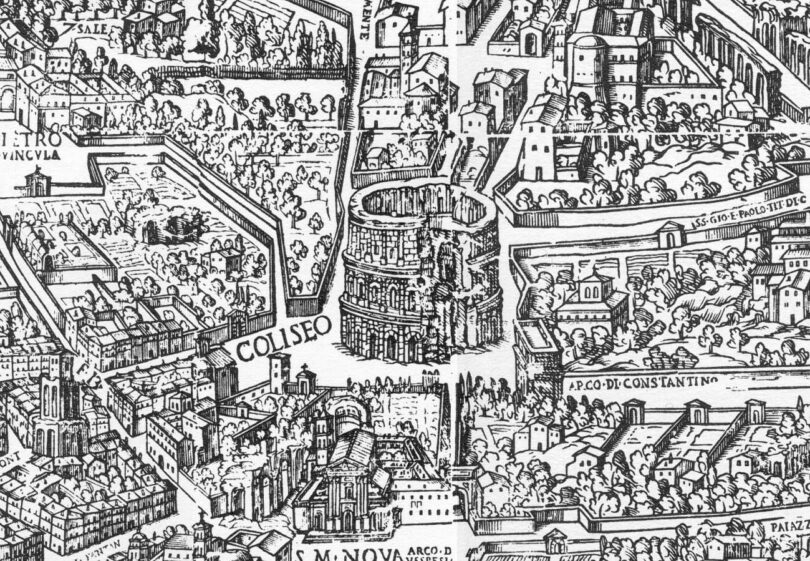

Did you know the Colosseum once became a fortified mansion? Indeed, at the start of the 12th century, the influential Frangipane family, who dominated areas from the Forum Boarium to the Palatine, established a residence within its eastern section. Unfortunately, no visible traces remain today, as 19th-century excavations erased these medieval imprints.

However, this remarkable structure was not merely reduced to noble residences. Over centuries, it transformed into a multifunctional communal space—housing chapels, craft workshops, animal pens, and even humble homes. Particularly striking was the Church’s influence, consecrating the arena as a holy site by establishing a chapel in the early 1500s and, later, installing the Stations of the Cross around its perimeter in 1720.

Giovanni Paolo Panini – Capriccio of Roman monuments with the Colosseum and Arch of Constantine

Despite the religious significance attributed by the Church, ironically, significant plundering of its stones persisted, particularly to supply materials for Rome’s grand structures such as St. Peter’s Basilica. This widespread quarrying activity severely impacted the monument, even contributing to the demolition of its southern ring.

Although Roman humanists passionately advocated for preservation in the 15th century, their calls largely fell upon deaf ears. True conservation efforts didn’t surface until much later, notably in the 17th and 18th centuries, when demolition slowed, giving way to tentative preservation strategies. The 19th century marked a pivotal shift: systematic excavations by prominent figures like Carlo Fea (1812-1815) and Pietro Rossi (1874-1875) uncovered the long-buried subterranean features, prompting removal of various chapels and shrines previously constructed within the arena.

Coliseum. Exterior was seen from the podium of the temple of Venus and Rome. 1860-1860. Biblioteca di archeologia e storia dell’arte (Rome, Italy)

The 1800s were also significant for critical restoration efforts. Between 1805 and 1807, Raffaele Stern constructed a robust brick abutment in the eastern section, while Giuseppe Valadier meticulously restored parts of the outer wall in 1827. Further significant restoration, executed by renowned architects G. Salvi and L. Canina between 1831 and 1852, substantially reinforced interior structures on both north and south sides.

By the 1930s, additional comprehensive restorations addressed the cavea (seating areas) and subterranean cellars, solidifying the Colosseum’s survival into modern times.

Reflecting upon this layered history, it’s clear that the Colosseum isn’t merely an ancient ruin—it’s a living testament to Rome’s complex narrative, continuously reshaped by human hands and shifting ideologies across millennia.

Leave a Comment