The triumphal Arch of Constantine was erected in AD 315 by the senate and people of Rome in honour of Constantine’s victory in 312 over Maxentius.

After defeating his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge Constantine moved his residence to Trier in Germany. He only returned to Rome three years later to celebrate the tenth anniversary of his ascent to power.

He inaugurated the arch that the Senate had erected in his honour on the long processional route followed by generals awarded a triumph: it ran from the Field of Mars through the city to the Temple of Capitoline Jove. With a height of 25.7 m. and a depth of 7.4 m., it is the largest and best preserved of Roman war memorials.

Statue of of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great – Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy.

As we learn from the inscription over the main arch, the monument was solemnly dedicated to the emperor by the Senate in memory of that triumph and on the occasion of the decennalia of the Empire, at the beginning of the tenth year of his reign on July 25, 315. The text reads,

IMP(cratori) CAES(ari) FL(avio) CONSTANTINO MAXIMO F(io)F(elici) AUGUSTO S(enatus) P(opulus)Q(ue)R(omanus) QUOD INSTINCTU DIVINITATIS MENTIS MAGNITUDINE CUM EXERCITU SUO TAM DE TYRANNO QUAM DE OMNI EIUS FACTIONE UNO TEMPORE IUSTIS REM PUBLICAM ULTUS ESTARMIS ARCUM TRIUMPHIS INSIGNEM DICAVIT.

Located on the Roman street along which triumphs passed, in the stretch between the Circus Maximus and the Arch of Titus, the Arch of Constantine is the largest honorary arch that has come down to us and is a precious synthesis of the ideological propaganda of Constantine’s age.

Among the historical references of the epigraph some scholars have interpreted «divine inspiration» (instin ctu divinitatis) as an allusion to Constantine’s «conversion» to Christianity and to the legend according to which he won the battle thanks to his vision of the «holy cross». The problem is actually the subject of much debate, as is the complex question of Constantine’s religious policy. In the middle of the twelfth century the monument was incorporated into the Frangipane fortress. It was restored and studied at the end of the fifteenth century and throughout the sixteenth, but the most significant activity in this respect dates from 1733, when many missing parts were replaced.

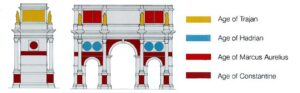

The three arches are decorated by marble slabs with reliefs. It was conceived and executed during Constantine’s reign as an integrated whole, utilizing mainly materials plundered from other imperial monuments. The compositional structure can therefore be divided into distinct chronological and stylistic sections, even though the choice of scenes reveals an evident thematic unity. On the main faces and short side of the arch there are reliefs from the ages of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, while the lower part presents ones from the reign of Constantine.

They alternate according to symmetrical patterns and by juxtaposing different events in the history of the Empire provide a valuable sample of the figurative language of imperial propaganda: “a concise overview of more than two centuries of history of official Roman art.”

The four panels from Trajan’s time originally made up a continuous frieze and must have decorated the Forum of Trajan as part of the facing of the attic of the Basilica Ulpia. It has recently been suggested that the rondels from Hadrian’s reign originally decorated the entrance arch of a sanctuary dedicated to the heroic cult of Antinoo, the young man loved by the emperor, who in effect appears in various hunting and sacrificial scenes.

The reliefs of Marcus Aurelius — to which three other panels of similar size and subject are now on display in the Palazzo dei Conservatori – come from the Arcus Panis Aurei on the slopes of the Capitoline hill, an honorary arch celebrating the emperor’s triumph over the Germanic tribes. The faces of all the emperors portrayed in the reliefs were remodelled to resemble Constantine, with a nimbus connoting imperial majesty. The face of Licinius, the emperor of the East, appears in the rondels with sacrificial scenes. In the panels from the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the head is Trajan’s and was inserted during the eighteenth-century restoration.

Arch of Constantine: The Political Use of Images of the Past

Constantine the Great wanted to be acknowledged and celebrated as the legitimate victor over his tyrannical rival, Maxentius, and the new arbiter of Rome’s future, and to this end chose a traditional monument that was deeply rooted in imperial history: the triumphal arch.

The inscription on the front of the arch represents Constantine as the restorer of the Empire, guided by divinity. The wars and triumphs of great emperors of the past cast an aura of legitimacy round his power and provided the political consensus needed for maintaining a stable government.

The great storied frieze running along the middle of the smaller sides of the arch and above the side-openings represents the Emperor’s feats: his departure from Milan; the siege of Verona, where he is crowned by a winged Victory; the defeat of Maxentius at the Milvian bridge; his entry into Rome; his speech to the population and a distribution of money.

In the last two scenes Constantine appears in the middle of the composition, disproportionately larger than the other figures, ranged symmetrically on either side and facing him, clearly indicating them subordination.

Emperor Constantine designed it to narrate his victories and crown his role in power, but decided to decorate it with older images taken from the memory of other buildings. Diocletian had done the same thing before him, composing the so-called Arcus Novus on Via Lata with plundered decorations.

The images of the past – the wars and triumphs of the great protagonists of the Empire – were the sign of an authority to which Constantine had to appeal to legitimize his power and guarantee the solidity of his government and his political consensus. The events taken from the victorious campaigns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius celebrated the present (the victory over Maxentius) in the context of a solid tradition of glory and power. In the constant dialogue between past and present, the memory of the great figures of the Empire suggested a temporal continuity between Constantine and the optimi principes of the golden age.

Leave a Comment